Fewer part-time jobs due to corona, paired with sky-high rents in university towns: Have students been able to keep their heads above water during the pandemic? Are there promising solutions out there for the many challenges on the horizon, or is the number of dropouts increasing? Read this article to find our response based on the findings from Fachkraft 2030.

Cologne, 03 March 2021. Almost a year has passed since the first lockdown was enforced in Germany to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Many students have already completed their second semester under pandemic circumstances, meaning they've spent roughly one third of the standard duration of a Bachelor's degree (6 semesters) studying during the global pandemic.This begs the question as to whether, and how, students are supposed to survive the economic implications of the pandemic alongside mastering the challenges posed to teaching.

We took a closer look at this topic in Fachkraft 2030 by comparing data from 2019 (September & October) and 2020 (August & September). In total, more than 28,000 students across Germany responded to the survey.

Fewer part-time jobs available as a result of the pandemic

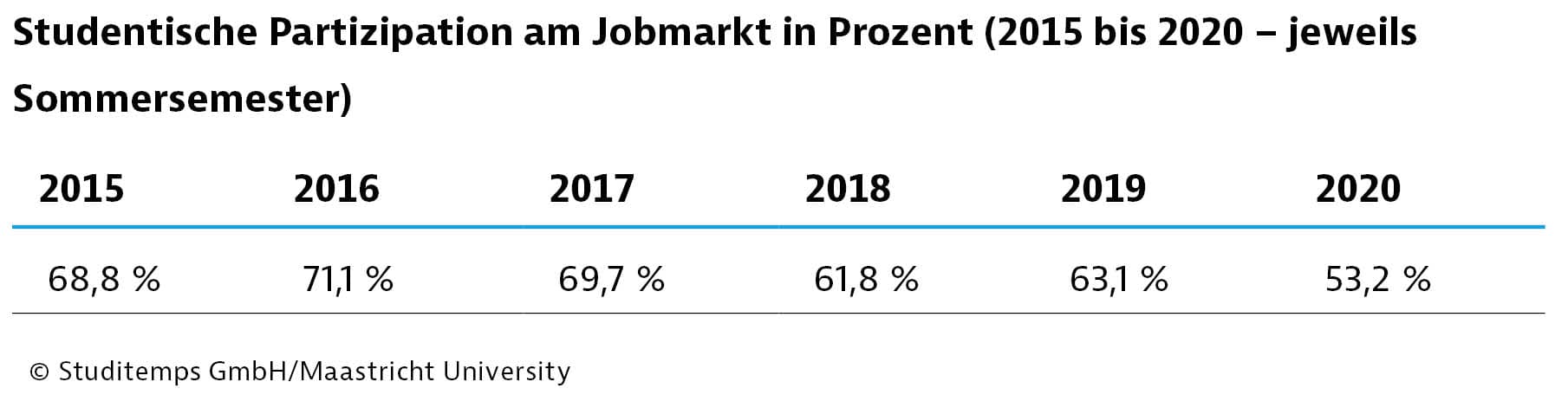

The initial finding hardly comes as a surprise against the background of a sluggish economy and increased short-time work. However, that doesn't mean it's not cause for concern: Student participation in the labour market decreased significantly in 2020 compared to 2019.

Meaning a decline of almost 10 percent, the lowest value recorded since the launch of the Fachkraft study series. This worrying development is further exacerbated by the fact that students traditionally find employment with part-time jobs in the food service industry, one of the hardest hit sectors during the pandemic.

Student participation: Was any regional variation observed?

Over the course of the pandemic, there has been a major drop in the number of students in employment. Comparing Fachkraft data from 2019 and 2020 demonstrated: Male and female students, as well as bachelor's and master's graduates, are all equally less likely to have a job. Only those who had attained a PhD enjoyed a slight increase in employment.

It's important to note that each region has experienced a varying number of COVID-19 cases. Which leads to the question of whether any variation has been observed at state level? The survey paints a clear picture in this respect:

‘The drop in student employment can most likely be attributed to the impact of the pandemic on the student job market. Interestingly, only 3% fewer students had a part-time job in East Germany than in 2019 – in the west this figure was almost 11% less. Perhaps this is down to the fact that Saxony, for instance, had one of the lowest infection rates in the summer and restrictions weren’t as strict, permitting events like smaller concerts or company parties and club events. Generally speaking, the economic hit in summer 2020 was relatively mild – shops and bars remained open. Nevertheless, the percentage of students in part-time employment had already fallen from 63.1% to 53.2%. I worry this figure may have since drastically increased once again as a result of the second wave and all it entails!’ – Eckhard Köhn, Studitemps CEO

Has the pandemic had an influence on the hourly wages of part-time jobs?

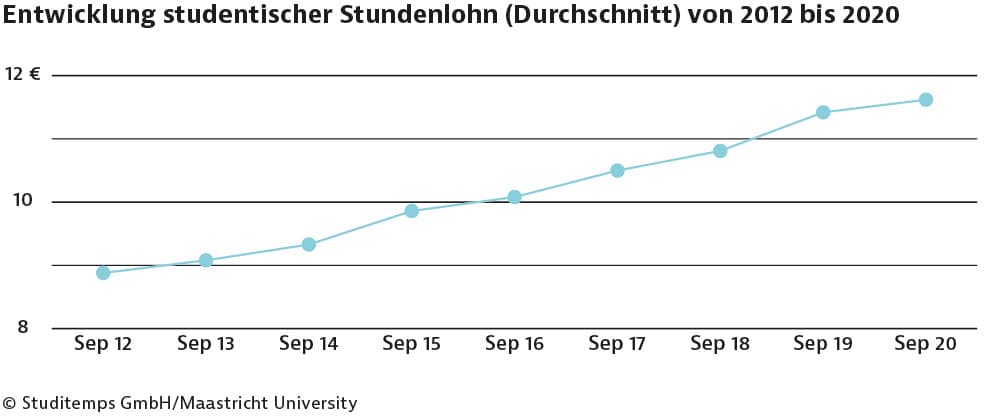

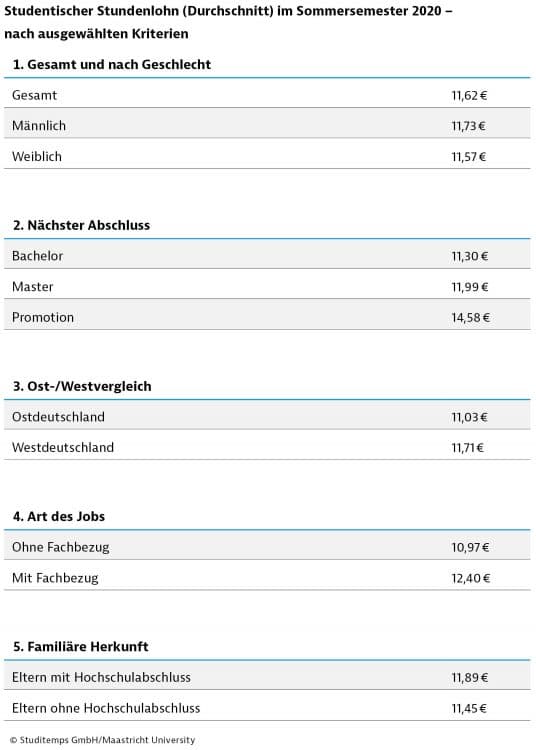

It remains to be seen whether less students are in employment. Students with a part-time job earned slightly more money on average compared to the previous year. However, this only constitutes a marginal rise from 11.42 Euros (2019) to 11.62 Euros (2020). Parallel to the lowest number of students in employment since Fachkraft launched, the wage increase is also the lowest reported in Fachkraft to date.

Gender pay gap

In the pre-pandemic era, between 2012 and 2019, student hourly wages in Germany rose by up to 6 percent each year. Now they've almost stagnated. That being said, there remains one positive take away: The gender pay gap, which has gained traction as a very important (contentious) issue over recent years, has continued to close: 4.5% (2019) to 1.4% (2020) for each hour worked. The average hourly wages in the previous year, i.e. €11.75 vs €11.23 changed to €11.73 vs €11.57 in 2020 (male vs female respectively).

While the pandemic is often viewed as a setback for gender equality, the reduced deviation in hourly wages between men and women offers everyone a (small) ray of hope in challenging times. However, the same cannot be said for the matter of familial background.

'Vastly different developments have been observed among various demographics: Students from academic households were more likely to keep their part-time job (or find a new one) while simultaneously earning more per hour on average compared to students from non-academic households (€11.89 compared to €11.45), which could perhaps be explained by the fact that they often work part-time jobs related to their field of study (27% compared to 22.6%). While this may be reason for this group to celebrate, it also reinforces the fact that the next generation benefits significantly from their parents’ connections. Accordingly, it's all the more important that students who don't come from an academic family receive opportunities – for networking, successful placement in student jobs and subsequently starting their career.’ – claims Eckhard Köhn

Be that as it may, even during the pandemic, part-time jobs and hourly wages only represent part of the overall picture. Another key aspect is the cost of living, primarily in the form of rent.

Stay home, pay the bills: Development of student rents

At first glance, recent trends may come as a shock. While students have long lived anything but cheaply, cold rent per square metre – rent exclusive of other costs, like heating – rose by around 8% from 12.55 euros to 13.54 euros between 2019 and 2020. Are students who have lost their part-time jobs due to the pandemic increasingly at risk of ending up on the streets as a result?

‘This may seem highly disconcerting at first glance, but it's not as black and white as it appears. As stated, cold rent per square metre has increased by 8%. However, this isn’t necessarily the result of rent increases. It could also be attributed to the fact that students moved into smaller flats – on average, their flats were 1 square metre smaller in 2020 than in 2019. While total rent may often be cheaper in smaller flats, the price per square metre is typically higher. However, the average total rent also increased slightly in 2020 (from €311 to €317). Meaning that the 8% increase in cold rent can be attributed both to rent increases and students moving into smaller flats with higher prices per square metre. All in all, rent hikes constitute another burden on already struggling students; this is hardly solidarity.’ – comments Eckhard Köhn

Digital universities

The start of the first ‘pandemic semester’ marked a major change for university students and society as a whole. Teaching went online virtually overnight, and nightlife options on campus and nearby disappeared without any sign of replacement. Along with rising rents, these factors also contributed to the fact that as of 2020, one in four students live with their parents. This marks an increase of 17% or 100,000 students compared to 2019. The pandemic has clearly done nothing to help solve the issue of the lack of affordable student housing near universities.

Did students have less money at their disposal in general?

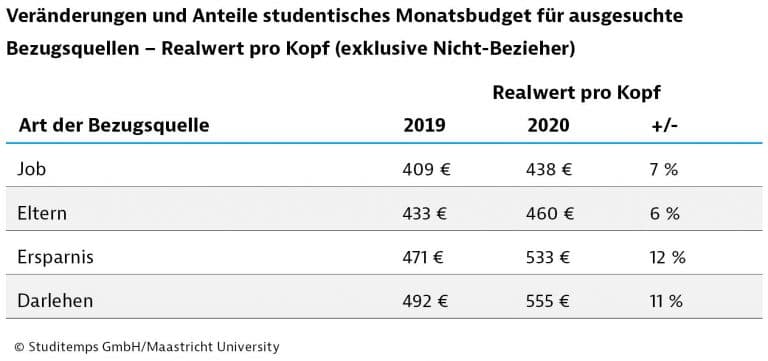

In 2019, students had an average of 847 euros per month at their disposal from various sources. In 2020, this amount increased to 859 Euros - twelve euros more. No absolute financial losses were experienced on a monthly basis. The average student budget actually increased slightly by around 1.4%. Likewise, students received more money from loans and credit lines, along with a rise in the average monthly BaföG payment amount – from €471 each month to €576.

However, as is often the case when we take a closer look, there is much cause for concern. Firstly, students have exhausted their (limited) reserves or taken on more debt and, secondly, fewer students received income from part-time jobs or support from their parents. Those who did have access to these sources actually received more money on average. As in other areas of education, the pandemic may only increase divergence among the student demographic, a development we have already encountered when looking at the distribution of part-time jobs.

A clear trend

‘There is a clear trend: Students are increasingly exhausting all remaining sources of money to help them compensate from losses in other areas, e.g. less support from parents needs to be compensated with more work. We have also witnessed this on our job platform. We’ve experienced more registrations and hires than ever before – at certain times, with an increase of up to 57%. However, this is out of necessity. Students need sources of income to account for the rising cost of being a student. For example, degree-related costs have gone up – from €106 per month to €134 (26.42%). This change could be attributed to increased expenditure on technical equipment, getting a better internet connection or equipping a home office.’ – Eckhard Köhn

Gauging the atmosphere: Are many students planning to drop out of university?

Luckily, the negative developments caused by the pandemic are yet to have an impact on the number of (planned) dropouts. So far, the probability of dropping out has only marginally increased between 2019 and 2020 – from 16.3% to 16.6%. The optimism felt by students about starting their careers is clearly reflected in their satisfaction with their studies, which has jumped from 76.1% to 76.7%.

Studitemps summary

Perhaps everything isn’t quite as bad as feared? Is it sustainable for students to just wait until the summer to work and refill their coffers? That would be great, but it’s not that simple. Our findings have shown that many students started drawing on their financial reserves in 2020, a situation that continues to worsen. Students' optimism is not infinite, particularly among those not blessed with access to their parents’ professional network and/or who are less well off. This worrying development requires a solution — at the end of the day, qualified and motivated students are crucial for rebuilding the economy in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Find more information on studying and earning money under pandemic conditions in our white paper under the same title.